|

|

So this is Greece and this is my village. I want to

introduce you to some of the people here and explain a little about

our life. A fishing village in Greece is the dream of urban people

everywhere, supposedly timeless and unchanged, as if these were

desirable qualities.

|

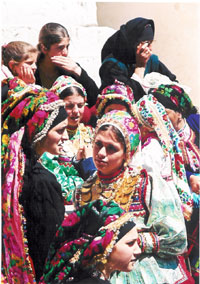

Traditional dress for the name day of a local church.

|

Maybe such places exist, but only in

the barren dreams of people made impotent by the thirst for money,

youth and success. We are not like that here. Maybe we are unique,

but I feel that we are real,that we have found something about the

possibility of living in harmony with a difficult landscape in a

difficult world.

I have tried to portray our community as it comes to

terms with change and deals with the burden of history. Wherever

possible I have tried to allow the people to speak for themselves.

If there are mistakes in style, or in substance, then the mistakes

are mine, for I am restricted in technique and running out of time

The visitors' perception of our village is limited.

To them it is always hot and always sunny. The smarter ones recognise

that it is nearly always windy too, but not much more. Those of

us that live here have to be more observant. We have to travel by

boat so we care if the wind is north or northwest, or even north

northwest. We know it is often calmer in the morning than in the

afternoon when the weather comes from the south and that, when it

is from the north, there is often a lull around dusk. We inform

our neighbours and ask for advice before we set off on a long journey

by sea. We do this because our weather can change in half an hour

and we know that if something goes wrong then someone from the village

will look for us if they know where to look.

In the winter, if we are lucky, it will rain. If we

are very lucky it will rain early and several times. Then we say

that the rains are useful and we know that our crops will grow and

there will be green across the island throughout the year. Two crops

are particularly affected by rain: wheat and olives. In many years

the winter rains are so poor that nobody plants wheat at all. A

whole cycle of traditions are held in abeyance; the ploughing, the

sowing, the reaping and the separating of the wheat from the chaff.

Of course, the flour made from our own wheat and ground in our own

windmills makes the bread baked in our ovens that much tastier.

|

| The Village fountain. Designed by the villagers

themselves, its painted ceramic tiles show scenes from life now

and in the past. |

Each of the stages of growing and harvesting,

processing and baking is accompanied by its own traditions, with

its own songs and words. Many of these words and traditions are

known only to the women and it is always with great pleasure that

we see young girls learning from their mother, grandmother and sometimes,

sitting in the shade of the oven, learning from their great grandmother

too. Good winter rains bring us good harvests and at the same time

our culture and our knowledge of the old ways springs up from the

soil anew. If it rains in late October or early November

we are especially pleased because the rain cleans the olives before

we pick them and that makes life easier. Our olives are small and

bitter, but they make fine olive oil and we produce soap too. Some

olive trees have their own names. We know when they were planted

and we know which of our forebears planted them and we talk to them

as we pass by. When we had the big fire and the pine forests and

olive groves burnt, we had problems with women who went into the

fields clinging to loved trees that were doomed. We had to drag

them screaming and weeping back to the village. We did not lose

any women, but we did lose many olive trees. Over the years we have

planted them again. A sign of renewal and hope and a wish for subsidies

from the European Union.

Through the winter we are fearful of the Sirocco, the

south wind that can do so much damage to our boats and even to the

houses in the village. Many times we have sat in the cafe watching

a storm when a big wave has come over the mole, over the beach and

the road and dumped water, sand, stones and muck right among us.

We lift up our feet as the water swirls under the benches and tables

and then it subsides and Anna comes, waving her broom and shouting

at us for being so stupid and at the sea for being so evil. It doesn't

take long to brush away the stones and at least the toilets get

cleaned. Winter here can be cold; not every day, but for days on

end. Our houses are cold too. Not many of the new ones

have chimneys and concrete is not as good an insulator as limestone

or slate. When the sun shines the women sit outside and the men

fight in the cafeneion for the next sunny spot, otherwise doors

are closed and the village too. Much work is done in the winter;

building, carpentry and farming too, but there are not so many of

us here to do the work. Much of the village is empty, as our children

go to school, or to university, and their families follow them to

the south of the island or to Rhodes or Piraeus, or maybe to the

United States. Grand parents and great grand parents follow too

and visit hospitals and old friends in far away places. I have never

been to Baltimore, but it must be strange to the people there that

Greek restaurants open in the winter and close in the summer so

that their owners and their families can come here to swim and fish

and have fun.

Springtime can be the best season. The sun starts to

warm our backs in the fields as early as February and within a few

weeks our fields and mountains are filled with flowers; green leaves

appear and herbs as well. There are red poppies and white neragoula

and narcissi too and those of us who walk in the forests marvel

at the tiny bee orchid, its flowers mimicking the bumblebee to attract

pollinators. Migrant birds appear; the small passerines, beeeaters

and rollers, hoopoes and birds of prey. From the cliff tops it is

possible to see eagles pass by; beating a passage over the sea,

heading north against the wind, flying close to the waves to give

them lift.

Booted eagles, short toed eagles, golden eagles come

to join our resident Bonelli's. We see black kites and longlegged

buzzards and once, huge and beautiful, an eagle owl heading north

to the Russian steppes. Cuckoos pass by and swallows, swifts, alpine

and pallid, and then we wait for the first tourists. These always

catch us by surprise. The rooms have not been cleaned since October,

the sheets are not washed, we have only half painted the house and

of course the rubbish brought by the winter storms has not been

cleared from the beach. But we are glad to see tourists;

they bring laughter and fun and sit in our cafe and our restaurants

and we renew old friendships and start new ones. Springtime is a

season of change for us.

Springtime can be the best season.

The sun starts to warm our backs

in the fields as early as February

By mid May the last Sirocco has ceased to blow and

the summer wind, the Meltemi, is blowing strong from the north.

The artichokes are ripe by now and the beehives double in population

every week or two. But it can be hot, far too hot. So we work in

the early morning, when the sun is not strong and the tourists still

asleep and the women bake bread at five in the morning and their

low voices mix with wood smoke as we sleep on roofs and balconies.

The summer wind is always from the north and it never

rains, but you will not see us working in the fields. There is some

activity however on the mountains around Avlona or in Saria, as

bee hives are moved to catch the thyme as it blooms. A good season

will bring reward and in this part of the island more than ten tonnes

of honey is produced and tourists can buy the real thing rather

than the cheaper varieties imported from Crete, or Denmark, or China.

In the cafeneion Anna will advise on the coolest place to sit and

where to catch a cooling breeze. But by August there is no room

for any of us in the cafeneion as the village is full of visitors;

Italians and French and Germans too, as well as our own people returned

from exile. So the hotels are full and most of the houses are occupied

and doors and windows that have been closed for months, or even

years, are open once again. Lights are on at night all over the

village and there is a smell of mothballs and sun tan lotion. Guitars

are played on the beach until the early morning and it could be

anywhere but here. So the people, who come for something unique,

find only something recognisable all over the world a holiday atmosphere.

Perhaps they are satisfied.

No matter, this time passes quickly and by the middle

of September the crowds have gone and the restaurant owners are

pleased to see you and we can go diving without being followed by

a flotilla of Italians hoping for us to lead them to the big fish.

And now there are kingfishers, a pair on each bay, speeding back

and forth exactly half a metre above the sea. They sit on rocks

and dive, neatly to seize atherinos, the little fish that cling

to our shores in late summer. Where kingfishers come from and where

they go I do not know. I have asked ornithologists and they cannot

tell me. I have never seen a nest, but I think they breed here,

late, in the rocks and in the cliffs. Soon they are gone too and

the passerines pass by at night, hunted and harried by Eleanora's

falcons as they hug the coast heading for Africa. The swallows head

south in late September and October and then the eagles and falcons

arrive in Saria and seek ever more powerful thermals. They go higher

and higher until they can see the weather to Crete and even Africa

and then they are gone. Herons and egrets stay for a while, then

one late evening, or on a bright night, we see the silhouettes of

skeins of birds going south and summer is gone.

We are back to autumn again and peace in the village,

but the olives need to be picked and crops planted and there are

ripe figs to be gathered and so much fruit. We need to fish to fill

the freezers, for the winter storms will come again from the south

and deprive us of sea bream and silver bream and red and grey mullet,

palamida and tuna. And of course we must fix that room and paint

the house to be ready for next season.

As for me, the time I like best is the onset of winter.

Sometimes, when the rains come, it is still warm enough to sit on

my balcony at night, in the dark and listen to the drops singing

on the roofs outside and smell the freshness of the pine forest,

a glass of whisky in my hand and a head full of memories. Or it

can be cold and windy and then it's time to go to Anna's and squeeze

through the door and sit inside and watch the men playing cards,

or tavli. An ouzo is called for now and I listen to the shouts of

the men and the storm outside and watch moisture trickle down a

windowpane. Then I know that I am really in the first chapter of

a fine novel by Kazantzakis and I am glad.

|

|